The Constitution of Scotland as a Civil Community- Alistair Livingston

When Margaret Thatcher declared that ‘there is no such thing’ as society in 1987, she was unwittingly rejecting a very powerful Scottish idea. It can be glimpsed in the Declaration of Arbroath and burst forth again in the Scottish Reformation. Called civil society it was refined by the Scottish Enlightenment, only to be stifled by conservative reaction to the French Revolution. Inspired by the Scottish Enlightenment and the French Revolution, Georg Hegel translated it into German as bürgerliche Gesellschaft in 1821. But by 1843, the reality of conservative reaction in Germany led Karl Marx to attack Hegel’s theory that a rational state would emerge out of civil society as ’the actuality of the ethical idea’. In Scotland, democratic reaction against conservative reaction -a negation of negation- has revived civil society since 1987. This new civil society has its expression in the grassroots Yes campaign. If this campaign -our campaign- moves beyond the September Revolution to ‘actualise the ethical idea’ in the Constitution of a new Scottish state, then Hegel may yet have the last word at the end of one history of Scotland and the beginning of another

I am going to begin with the long version of Margaret Thatcher’s society quotation.

I think we have gone through a period when too many children and people have been given to understand “I have a problem, it is the Government’s job to cope with it!” or “I have a problem, I will go and get a grant to cope with it!” “I am homeless, the Government must house me!” and so they are casting their problems on society and who is society? There is no such thing! There are individual men and women and there are families and no government can do anything except through people and people look to themselves first. It is our duty to look after ourselves and then also to help look after our neighbour and life is a reciprocal business and people have got the entitlements too much in mind without the obligations, because there is no such thing as an entitlement unless someone has first met an obligation. [Woman’s Own magazine, 1987]

From a Scottish perspective, Margaret Thatcher’s rejection of a thing called ‘society’ is very revealing, since the idea of a ‘civil society’ existing between individuals and families and the government or state was developed during the Scottish Enlightenment- for example in Adam Fergusson’s 1767 ’Essay on the History of Civil Society’. Ten years later, in ‘The Wealth of Nations’, Adam Smith linked civil society to modern economies, contrasting it to the feudal system where production was governed not by market forces but by coercion and force. For Smith the ‘feudal system’ was the economic exploitation of peasants by their lords, which led to an economy and society marked by poverty, brutality, exploitation, and wide gaps between rich and poor.

In Scotland, the feudal system began in 1124 when the first grant of land to a Norman knight was made by King David I. The charter made Robert Bruce lord of the land and people of Annandale. David had spent ten years in exile in England where he was exposed to the theory of feudalism. This held that God had granted kings absolute ownership of all the lands and people of their kingdoms. It was used by William the Conqueror to place his Norman followers in power over the English.

Two hundred years later, the seventh Bruce lord of Annandale was King of Scots. But despite his heroic efforts in securing Scotland’s independence from England, in 1320 the Declaration of Abroath placed a contractual obligation on King Robert I.

Yet if he should give up what he has begun, and agree to make us or our kingdom subject to the King of England or the English, we should exert ourselves at once to drive him out as our enemy and a subverter of his own rights and ours, and make some other man who was well able to defend us our King…

By placing this limit on the absolute power of a king to rule, the Declaration was also challenging the idea of feudal superiority which allowed English kings from Edward 1 to Henry VIII to claim that Scottish kings were historically their feudal vassals.

For the next 240 years this contractual theory of kingship lay dormant until it was revived by the Scottish Reformation. The key figure here was George Buchanan who tutored the future King James VI. Drawing on Protestant religious theory, Buchanan argued that the source of all political power is the people, that the king is bound by those conditions under which the supreme power was first committed to his hands, and that it is lawful to resist, even to punish, tyrants. His pupil strongly disagreed.

As soon as he was securely established as King of Scots, James VI drew on the tradition of feudalism established by David I to argue for the divine right of kings to rule. James refuted Buchanan, holding that a king owns his realm as a feudal lord owns his fief, because God made kings arise “before any estates or ranks of men, before any parliaments were holden, or laws made, and by them was the land distributed, which at first was wholly theirs. And so it follows of necessity that kings were the authors and makers of the laws, and not the laws of the kings.” In James’ theory God had granted kings a divine right to rule.

While James had the theory, his son Charles had the practice. Because so many Scottish kings and queens had spent their childhoods more or less as hostages to different noble families, it had become a tradition that between the ages of 21 and 25 a king or queen of Scots could revoke any grants of lands made when they were minors. Charles I became king in March 1625 and would reach the age of 25 in November that year. To avoid going to the English parliament for money, Charles came up with a cunning plan- he as Kings of Scots would pass an Act of Revocation, but one backdated to the death of James V in 1542.

By a stroke of his royal pen, all the Crown lands in Scotland- including former Church lands and the teinds, a tenth share of the produce of the lands- disposed of since 1542 would revert to Charles. His plan seems to have been to then re-grant them, for a fee, to their current owners, but this was not made clear at the time. Instead, by this demonstration of his absolute power, Charles infuriated the most powerful land owners in Scotland and the Church of Scotland. The landowners were outraged by the prospect of losing huge tracts of ‘their’ land and the Church was convinced that Charles would use the teind money to pay the salaries of bishops rather than parish ministers and parish school teachers.

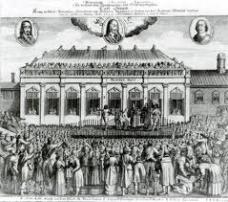

As it turned out, Charles was unable to enforce the Revocation Act. But fatally for him, by managing to unite Scottish landowners and the Scottish church in opposition to his rule, Charles laid the ground for the Bishops Wars of 1639 and 1640 which in turn led to what is sometimes still called the English Civil War. but is more correctly described as the War of the Three Kingdoms. Sadly for Charles, God turned out to be a parliamentarian and Charles I was executed on 30 January 1649. The Parliament of Scotland immediately proclaimed his son Charles II King of Scots on the 6 February but Charles had to wait until 1660 before he was restored to the English throne.

Execution of Charles I

One of the first acts of the Parliament of Scotland after Charles II was safely established in London was to summon the Reverend Samuel Rutherford to appear before it on a charge of High Treason. Rutherford’s crime was to have written a book called Lex Rex- the Law of the Prince, published in London in 1644.

Here I will throw in a snippet of movie history. Between 1627 and 1638, Rutherford was minister of Anwoth parish in the Stewartry and remains of his church feature in the now classic horror film the Wicker Man.

Lex Rex is a complex and deeply learned text, drawing on aspects of classical philosophy as well as theology. Remarkably for a Calvinist Presbyterian, Rutherford even quoted approvingly from Jesuit sources in developing his argument. So what was Rutherford’s argument? It is that although God in his wisdom, acting through natural law, requires that people, ‘being reasonable creatures united in society’ should have a system of government, the exact form such a government takes is not specified by God so may be a republic rather than a kingdom. If the form of government is a kingdom, the people limit the power of their king measuring out ‘by ounce weights, so much royal power, and no more and no less.’ Royal power measured out in this way is also conditional and the people ‘may take back to themselves what they gave out‘ if the king breaks his agreement or covenant with the people by becoming tyrannical.

For Charles II and his new regime, the philosophical and theological complexities of ‘Lex Rex’ were irrelevant, all that mattered was that Rutherford’s book provided a justification for the rebellion which led to the death of Charles I. Only Rutherford’s natural death in March 1660 saved him from the likely fate of public execution for High Treason.

Although Rutherford’s ‘reasonable creatures united in society’ echoes Buchanan’s ‘civil community’ and is close to the idea of ‘civil society’ advanced by Scottish Enlightenment thinkers, Rutherford did not develop the idea in his later writings. Instead, in response to the political ferment unleashed by the civil war in England, which included the democratic demands of the English Levellers, Rutherford retreated into his religion. As his biographer put it ‘Where there was a conflict between the principles of natural reason and the logic of true religion, religion took precedence.’

Charles II was more sensible than his father and didn’t lose his head in a crisis. On the other hand he was not amused when Calvinist Presbyterians in the west of Scotland, following Rutherford’s religious principles, resisted his attempts to turn them into Episcopalians. The struggle between Presbyterians and Episcopalians turned into a 28 year long low intensity civil war.

This civil war ended when James VII, on his second attempt, managed to flee London rather than confront his son-in-law William of Orange and his invasion force. As soon as news of James’ flight reached Dumfries, a new town council was elected on 26 December 1688 and unanimously voted in William of Orange as their new king on 9 January 1689. In Edinburgh a special convention met in March 1689 to decide, following Lex Rex, between the rival claims of James VII and William of Orange. Again, if less unanimously than in Dumfries, William was chosen as Scotland’s new king. James and his supporters refused to accept this decision. It was to take the brutal defeat of James VII grandson and his army at the battle of Culloden before all hope of a second Stuart restoration perished.

Although the first glimmerings of the Scottish Enlightenment had already emerged, for example with David Hume’s ’Treatise on Human Nature’ published in 1740, it was only after the defeat of the Jacobites in 1746 that it was able to flourish.

A key theme of the Scottish Enlightenment was the idea of a ‘civil society’ existing between individuals and families and the state. If there had still been a Scottish state with Edinburgh as its political centre, this idea might not have arisen. Scottish intellectuals would, as members of a privileged elite, have been part of this Scottish state. But with the new Union state of Great Britain centred on London, the dispossessed Scottish professors, lawyers and ministers had to re-invent themselves as members of their own stateless civil society.

Since they viewed the new Union state as a continuation of the English state English intellectuals did not face this problem so had little interest in ‘Scotch philosophy’. The Scottish Enlightenment was more favourably received in France and Germany. Immanuel Kant claimed that David Hume ‘roused me from my dogmatic slumber’ and Georg Hegel was another German philosopher who was influenced by Scottish Enlightenment thought. Hegel, however, developed his political ‘Philosophy of Right’, published in 1821, after the French Revolution and the Napoleonic wars. In Hegel’s version, civil society emerged out the disintegration of the family as the focus of ethical life and in turn a rational state will emerge out of civil society as the ‘actuality of the ethical idea’.

What Hegel hoped was that Prussia would be able to modernise and become a rational state without having to undergo a bloody revolution. But by the time he wrote an essay on the English (that is British) Reform Bill just before his death in 1831, Hegel was less optimistic. He feared that the forces unleashed by industrial capitalism would lead to revolution rather than reform -at least in Britain. Then, while Friedrich Engels was noting the revolutionary potential of the working classes in Manchester, in 1843 Karl Marx wrote a lengthy ‘Critique of Hegel’s Doctrine of the State’ focussing on the gap between Hegel’s ideal model of the emergence of the rational state out of civil society and the reality of actually existing states.

In Britain, reaction to the French Revolution saw a rapid closing down of enlightened political debate. In England, radical poet William Blake was brought to trial in 1804 on a charge of sedition. In Scotland Robert Burns faced a similar threat ten years earlier and had to disguise support for reformer Thomas Muir and the French Revolution within the language of Scottish patriotism in ‘Scots Wha Hae’. What did survive from the Scottish Enlightenment were the ‘laissez faire’ theories of political economy advocated by Adam Smith, James Steuart and Galloway’s own John Ramsay McCulloch. As the new capitalist economy expanded, Karl Marx moved on from critiquing Hegel’s theory of the state to publish the first volume of ‘Capital’- his critique of political economy, in 1859.

In an echo of Rutherford’s Lex Rex, Hegel’s civil society was supposed to give rise to a rational state in the form of a constitutional monarchy which Hegel preferred over a republic. But, as Marx recognised, Hegel’s ideal account of history did not give enough weight to political economists’ version of civil society as the arena where economic activity takes place.

By the 1840s, the capitalist class which emerged out of civil society had captured the leading European states and turned them into irrational instruments of their economic interests.

Fast forward to 1945 and we find that following the trauma of the great depression and a second world war, a form of social democracy began to emerge in front of the Iron Curtain. Over the next 30 years the boundaries between civil society and the state became blurred and something like Hegel’s rational state began to emerge. Then in the 1970s, the post-war social democratic consensus began to unravel. In the UK this led to the election of Margaret Thatcher‘s government in 1979. Having re-captured the state, the forces of a re-energised capitalism now called neo-liberalism began to demolish the socialism of civil society and -as in the infamous quote I began with- to deny the very existence of society.

But if there is no such thing as society, or more exactly, as civil society, why are we here today? I think the answer can be found in the difference between Scottish and English reactions to Margaret Thatcher’s Poll Tax. In Scotland, it gave rise to a popular movement of collective resistance to the tax. It also focused Scottish civil society on the need for constitutional change which led to the creation of a devolved Scottish Parliament ten year later.

I was living in Hackney in London’s deprived east end in 1990 when the poll tax was introduced. I was involved in the local anti-Poll tax campaign and planned to stand as an anti-poll tax Green Party councillor in that year’s local elections. On 8 March the council met to set the poll tax rate for Hackney in a boarded up town hall surrounded by a wall of police confronting an increasingly agitated 1000 strong crowd. A three days earlier, Harringey had set their rate and there had been a minor riot. Now everyone was expecting a riot in Hackney.

I had, rather naively, planned to give an election speech to the crowd so was wearing my wedding suit. There was a BBC London film crew there and I was chatting to them when they suddenly got busy, anticipating trouble. So I moved on to the steps in front of the town hall to get my speech in before the trouble started. I managed to say ‘If you want to get rid of the Poll Tax, don’t get mad get even and vote Green’ before the police suddenly moved forward from behind me to push the crowd away from the town hall. The only response I had from my election speech was a young punk woman in the crowd shouting back at me ‘It is too late for that now’.

I then went home then but my wife stayed on to report later that a riot had broken out. McDonalds burger bar was smashed up and Paddy Ashdown, who had been giving a speech in the Assembly Rooms behind the town hall, had his car attacked by the crowd and 38 people were arrested.

Poll Tax Riot Trafalgar Square 31 March 1990

Compared with the major Poll tax riot which took place in and around Trafalgar Square on the 31 March when there were 350 arrests what happened in Hackney was a minor affair. However, not wanting to be arrested for giving my speech in Hackney, before hand I had contacted the local police, the council, several UK and foreign journalists and even Paddy Ashdown’s office. All the people I spoke to realised that there was going to be trouble, but seemed helpless before the rapid movement of events. That the massive 31 March Poll Tax rally would lead to a major riot now seemed a certainty. An unexpected outcome of the Trafalgar Square riot was the enforced resignation of Margaret Thatcher in November 1990.

Reflecting on the dramatic events of 1990, it is possible to see in the very different reactions to the Poll Tax north and south of the Border the first signs that Scotland and the rest of the UK were beginning to move apart politically. In Scotland the economic hammer blows of Thatcherism reforged a powerful sense of Scotland as a civil society. Across most of England, the same hammer blows fractured the post-war consensus and fragmented civil society.

In Scotland the evolution of civil society has continued. Tonight I have traced the history of Scotland’s civil society from its origins to the present. Our task now is to make history, to have our September Revolution and carry that revolution through to the actuality of the ethical idea, embedded in the written Constitution of a rational Scottish state.

This is an excellent article and well worth reading. You might like this book, which deals with ‘actualising the ethical idea in a rational Scottish state’ (although its framework is Aristotelian rather than Hegelian, so it uses the language of flourishing and the common good instead): http://constitutionalcommission.org/blog/?p=348